Why Science and Policy Need More Stories to Compete with Fake News

Kevin Padian believes that better scientific storytelling, with the intent to connect with people, can help build public trust in science.

- InterviewPost-truth pandemic

- February 6, 2023

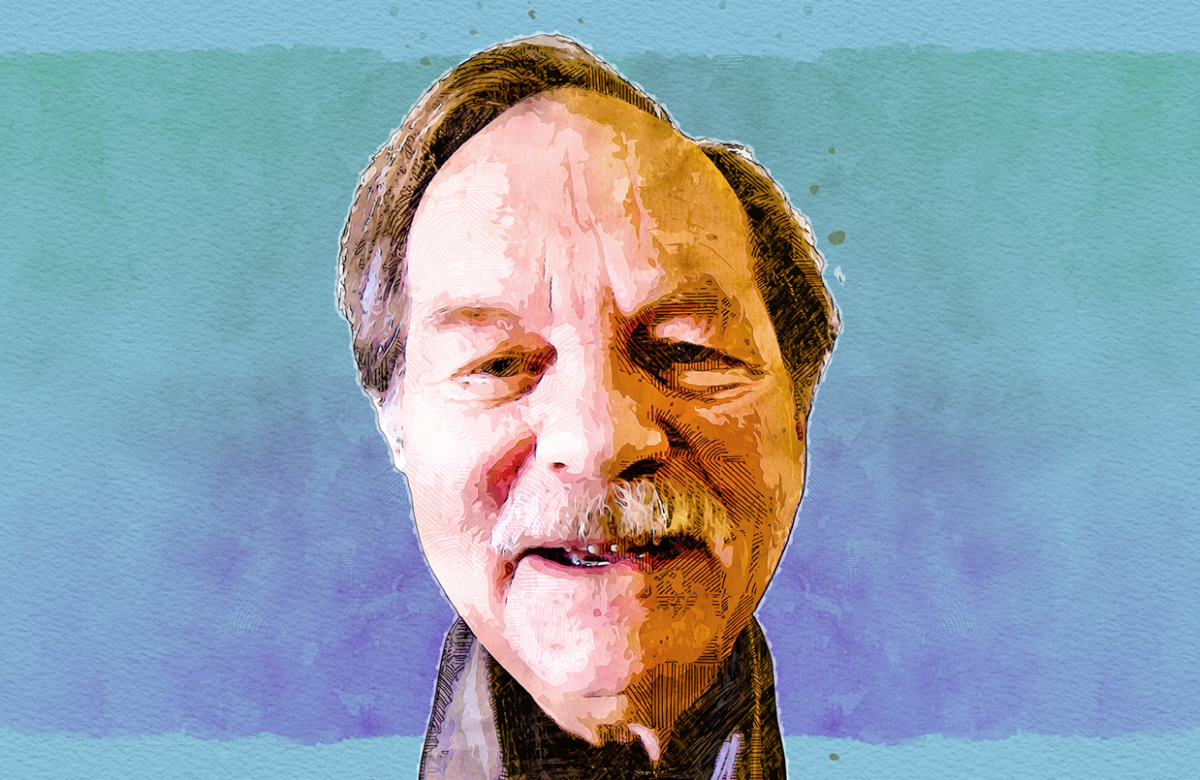

Despite being a giant in his field, Dr. Kevin Padian is unassuming on meeting him. With the classic disheveled hair associated with the stereotype of the absent-minded professor, he is relaxed, comfortably lounging in a hoodie while chatting. But beneath this modest exterior lies a sharp, inquisitive educator’s mind. In his role of Professor of Integrative Biology at the University of California, Berkeley, Kevin has focused his academic work on macroevolutionary problems such as the origins of flight and the evolution of birds from theropod dinosaurs. Outside that sphere, however, he has remained a steadfast proponent of improved science education and public discourse, serving as an expert witness for the plaintiffs in Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District which focused on the teaching of evolution versus “intelligent design” in schools, and during the 1990s, he contributed significantly to the California Science Framework program and the review of many science textbook programs in K-12 schools. In 2003, he earned the Carl Sagan Prize for Science Popularization. Kevin has authored nearly two hundred scientific articles, including “Narrative and ‘Anti-narrative’ in Science: How Scientists Tell Stories, and Don’t,” and is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

ScienceTalks spoke to him about his views on science communication and how improved communication can help address trust in science, a major source of suffering during the pandemic. This interview was conducted in January 2022 and has been edited for length and clarity.

To start, could you give us an overview of your career?

It’s funny: I went into science because I thought that it was taught very badly when I was a kid. In those years, the 1950s and ’60s, there was competition between the United States and Russia on the space program. Once Russia had launched its first satellite, the United States realized that they could fall behind very quickly because they didn’t have the science education program that they thought Russia had. In those days, they tried to institute more rigorous science teaching in grade school for children of ages 10, 12, 14, and 16. This had mixed success. We learned a lot of things that were very complex, like the Krebs cycle. But we did not learn about the birds and the bees and the environment around us and the geology and how the area we lived in had come to be. It was all very technological and meticulous science about how things work, photosynthesis, and things like that. When you are 10 or 12, you don’t really care about that, but you might want to know why the sky is blue.

Anyway, I didn’t intend to major in science. When I was in college, a really great professor inspired me, and so I went into a field which had always interested me but I had never been taught – evolution and related things. It stayed with me. When I finished my bachelor’s degree, I got a degree in science education because I wanted to teach science in a way that I thought would be more engaging than how it had been taught to me.

After a couple of years, I realized I really didn’t think I knew enough science to be a good science teacher. I went back to graduate school and got a Ph.D. that priced me out of being a high school teacher, but I got this job at Berkeley. Along the way, I learned to love research and research questions. What I love about doing a research project is the story that you can tell when it’s done and what you can teach people and how it can make them more aware of things. I have had the privilege of enjoying my research and my teaching career. Of course, by teaching, I include trying to influence public education curriculum and the integrity of science in the public arena.

Why did you pick evolution? Did it have anything to do with general public interest, compared to, say, mathematics or physics?

Or plant ecology, which is a lovely field. I love plant ecology. But that field is not assaulted by religious fundamentalists. People who study evolution are [assaulted], especially people who study the big picture of evolution, which we paleontologists do. They don’t like that. Up to a point, the creationists and anti-scientists will accept things like changes within whatever they consider species or what they call created kinds, but they don’t like the big transitions. They don’t like my work because that’s what I do. They are especially not happy when I correct them on the misleading things they write about the kind of problems I work on. They don’t want to be corrected; they want people to think this is a matter of opinion.

This is especially common in the United States, but the thing about our country, as I think the British publisher Andrew Melrose said, is that it is founded by two kinds of colonists, the one that’s just trying to get away from religious persecution and the other that is trying to get away from religious persecution and once they get here they persecute anyone who doesn’t agree with them. We have our “founding fathers,” Jefferson and the like who were children of the Enlightenment. They wrote in an extremely broad, open, philosophical way. Then we have the pilgrims who came because they were being persecuted for their religion. They wanted to set up religious societies. This has been the great war in the United States ever since. We say there’s a separation of church and state, but I think half the time we don’t believe it.

As a result, I’ve been attacked for my work. Throughout my career, the religious fundamentalists understood that what I was doing was dangerous to their worldview. The scientists working on these projects understood the threat it posed if people could find in the fossil record over millions of years animals that had transitional features in evolving new adaptations, like my area of interest, flight. I mean flight is a big thing; it’s very difficult to evolve. Anti-evolutionists would love to pretend that there’s no way to do it. But of course, there is. We know that it did happen because we can see the progression morphologically from the dinosaur-like animals that became birds and transitions like that. I think we have a pretty good idea how flight evolved, although there are different variations on the theme. In any event, the creationists don’t like that stuff at all.

I’d like to get your view on the COVID-19 pandemic situation. In some ways, there seem to be parallels between the conflict between your work and creationists and the conflict between medical scientists and conspiracy theorists producing fake news and weird theories.

It’s different dealing with anti-vaxxers and people like that, or with creationists who are denying science. In the United States, we have maybe 30% of the populace who are what we would call Enlightenment-oriented, that is, rational about scientific inquiry and understanding. About 30% of the people are fundamentalist Christians or fundamentalists of other religions who reject that rational approach. One thing is not to have a public debate with an anti-scientist or religious fundamentalist, because then your worldviews are on the same plane and that’s not valid. It’s important for any side of a discussion to establish what you think you understand and why, what the rules are for establishing this understanding, and above all, how you would know if you were wrong. Other scientists are not just free but encouraged and obliged professionally to tell another scientist when they think you are wrong. Religion and other kinds of worldviews have no such constraints. Anyone can say what they like. But a scientist asks every day how they would know if they were wrong, because if you don’t ask yourself that, your friends and colleagues are very happy to point it out for you.

The remaining 40% of the population are in the middle, and those are the people I am trying to get to. My arguments to them are about what makes sense. The only way I know how to do that is to talk about how we know what we know. Here are these cool fossils and plants and animals that we have today that tell us all these things, and here’s how we produce our information, here’s how we test our hypotheses, and here’s how we publish under peer review to ensure (one hopes) that our findings are reasonable. That kind of persuasion has no agenda against religion. I’m not trying to convince anybody who rejects my research findings; I’m just trying to show people what we think we know, how we do it, and how we think about it.

With COVID-19, politics entered the mix because many people were confused by new and emerging medical results and government policies. Changes in approaches and recommendations as new information was learned made some people intellectually uncomfortable: how can science and medicine be trusted if they keep changing their prescriptions? Religions operate on the basis of tenets that are more or less unchanged or unchangeable, whereas science is just the opposite: we’re constantly testing what we think we know and comparing new findings against received understanding. Sometimes scientists don’t do an adequate job of explaining why new evidence suggests that we need to change course. I think that as scientists, when we tell good stories, we can often be more persuasive to people than simply explaining our methods and findings.

We tell two kinds of stories in science: we tell stories about our research and the science itself and we tell stories about us. Many times, the average person will connect with a scientist if they can describe how they came to be interested in their field, say, either through a great teacher or learning a cool new topic. It appealed to my philosophical side because I realized that you could test this stuff. It wasn’t just things that people believed or interpreted, like you do literature or music. It was something that the community had to interpret and understand. It was science; it was knowledge by the community, with development and buy-in and correction. I thought that was pretty cool, but with the COVID stuff, the researchers who are explaining what they are doing have a hard task. I think they’re doing a wonderful job.

And I think much of the American media have fallen down on the job. You have people like Anthony Fauci explaining things in the simplest and most consistent and most honest terms possible. Here’s what we know, and here’s what we think we know. Here’s what we are suggesting people do and why. Sometimes, new things come up. You get a new variant, you get more cases, people stop getting vaccinated, or there’s a surge. Then the message has to be changed. That’s the way science works: you get more evidence and you change your mind if necessary. But that’s a tough approach to understand for people who have an authoritarian mindset: the experts have to be right and infallible. If they change their prescriptions, they’re not infallible, so why should we trust them? This is perfectly natural.

Here’s an example of confusion generated by new information. At the beginning of the pandemic, when there weren’t very many masks, the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] asked people not to buy up all the masks. Leaders focused on supplying the masks to doctors and nurses, who were so greatly at risk for infection while they tried to help the infected. Once the supply was replenished, they encouraged the lay public to buy masks. But the press allowed media mavens, who you would have thought knew better, to say this was a switch in policy. It’s not a switch in policy; it’s a modification of advice based on new events and information. The reputation of the CDC, previously the most trusted institution in medicine pretty much worldwide, was greatly weakened under Donald Trump. He is responsible, as far as I am concerned, for hundreds of thousands of deaths in this country alone because he didn’t want the pandemic to make himself look bad in the polls. This public health nightmare is not down to scientists.

Some years ago, George Lakoff, a great linguist and rhetorician in my university, came up with the concept of a truth sandwich when reporting on Donald Trump. When reporting on one of his lies, you state what Trump said. Then, you state the facts of the case, and then you explain why what Trump said was a lie. That’s the truth sandwich, and it is what the media should have been doing throughout his presidency. But far too much, they acted like these two views were intellectually equal, and they are not. People are welcome to their opinions, to their beliefs, to their actions. But there were so many examples of people who said that we don’t need to vaccinate, that it’s all a hoax, and then they showed up at the hospital sick to death with COVID and had an eleventh-hour conversion.

And a lot of medical and non-medical people at the time said, I don’t want to see you. Please go home. You don’t get to infect the doctors and nurses. You have made your choice, and all of our hospital beds are occupied because of you. People who need transplants, cancer treatment, and major surgeries are having trouble getting beds because of you. Is this fair or reasonable?

Finally, I think we need to recognize that balanced is not always fair. The epidemiologist should not be balanced 50:50 in the press with the uneducated blogger in his mother’s basement. It’s not fair to the public to treat these views as of equal relevance to the question at hand. In my (admittedly biased) view, the function of the journalist is to assess the problem of the day and present the complexities.

In this vein of balanced not being the same as fair, it seems that some journalists are making the news unnecessarily complicated, especially in the United States. Could you discuss why scientists may be having problems getting their message out effectively?

I am in a very high-powered department, and my colleagues at other departments have wonderful teams as well. What I have observed in all these years is the tendency for many of my colleagues to produce graduate students who are just like them, clones of their mentors. I mean, they have the potential to take science in wonderful new directions, but their professor feels successful when they produce a student that does great research in their field, goes to conferences, and produces papers and talks on the subjects. I risk annoying my colleagues when I state that this is just talking to ourselves. This has no impact whatsoever, except on a few people that work on what you work on. No one else cares because you haven’t made it important.

You have been given all this by society. Wouldn’t it be nice to give back by trying to learn how to communicate the importance and the fun of what you are doing? Let people know that science is just going into laboratories and coming out with discoveries. It’s a process of discovery, of working together, coming up with ideas, making mistakes and modifying your ideas, and coming back to the table.

My colleagues think it’s really great when their students get terrific academic jobs in other universities. I think that’s great too. But I think it’s equally great when one of our students goes into journalism, science publishing, media and communication, or government. As a government advisor on issues related to their field, they’ll actually influence people, change issues, and give perspective gained from one of the best departments in the world. Why is that less important than following your advisor and producing one hundred papers on the same old stuff? But the great thing I’ve observed in the past decade is an increasing trend for grad students to want to become more involved in “science and society” activities, and to spend more time helping the public understand science and why it’s important.

How do you think science can make its stories stronger to improve communication?

That’s a great question. In the case of COVID-19, I think it’s not so much down to the scientists as it is to the clinicians. Scientists work in labs, and they develop technologies like mRNA and implement ways of tracking the coronavirus, and that doesn’t connect with most people. Just following what I said before, it would be better for people to see more videos of people in COVID wards who are on the brink of death and asking for vaccinations. That’s important. They should also be shown the burnout and stress that our healthcare workers face. These people are quitting their jobs and dying by suicide. They have PTSD. It’s like they are on a battlefield. I think that if these clinicians were filmed just talking about what it’s like to be in an atmosphere like this, that would make a mark. These are people who they have known for years, who have gone to school with their kids. Those stories are going to make a difference in a way that no objective discussion about science can make. And that’s because COVID is not about science; it’s about hearts and minds.

In one of your papers, you discussed the different domains of knowledge: scientific, religious, and secular. Given that you say COVID is about hearts and minds, what do you see as the role of these three different domains of knowledge?

For decades, religious people have written about the war of science against religion, and they framed it in terms of battle metaphors. This is a common theme through the creationist movement in the United States through the twentieth century. If you have science, religion, and the secular realm, ask what each of those domains has to say about the COVID crisis? Science has to figure out how the disease works so that it can be stopped. The secular domain, which includes governments or societal groups, also have their way of looking at the problem and adjusting their actions. But I don’t see any role whatsoever for the domain of religion in this pandemic. All religions can ever discuss is their own theology; it has no claim on any other kind of knowledge.

What is odd to me in the secular realm is that government officials have now had to deal with citizens claiming religious exemptions from vaccination. Well, on what religious grounds do you not believe in vaccinations? There is no standard religion that I know of that specifically states or even implies anything like that. People can claim personal religious beliefs, but at least in the United States, those have limits.

For example, someone may say that their personal religion is such that they do not feel bound to pay income tax to the United States. Good luck with that because you will be put in jail. Now, the government may not forcibly vaccinate you. But they have the right to exclude you from any public forum if they so choose. Yes, that’s very unpopular, but sickness and death are also unpopular. When we know as much as we know about the course of these diseases and variants, it’s not unreasonable to take some precautions. In our country, we still allow unvaccinated people to get on airplanes [recall this interview took place in early 2021], but not all countries are like that. That’s for the secular realm to decide.

Can you elaborate on the role of scientists in such situations? How much should the public expect specific directions and unarguable truths? There may be some confusion regarding what people should expect from the scientific community.

You’re right. All scientists can do is more of what Fauci does and explain the science to people and make recommendations about the most prudent course to reduce infections and deaths. But unless you live in a very autocratic government state, it’s difficult to make people do everything. The Chinese can do this with some effectiveness, but they are the exception. Most governments can write out laws, such as the necessity to wear seatbelts or drive on the right or left side of the road, or to obey traffic lights. You can outlaw smoking in public buildings. But the consequences of these acts are different. First of all, we say we don’t want the public to smoke in public buildings because secondhand smoke is bad for other people. There is a consequence to other people. If you decide you can drive on whatever side of the road you want or you don’t stop at red lights, there are consequences to other people. You could drive all you want, crashing your car at 100 miles per hour without a seatbelt or airbag, flying through the windshield, hurting only yourself. Do people have a right to do that? I would say yes. They have a right to hurt themselves if they want to, but they don’t have a right to put that on the public or to endanger others.

Emergency room doctors sometimes call motorcycle riders “organ donors.” If they don’t wear helmets, as they are required to by law, and they crash, generally their heads get messed up. When they die, their uninjured organs can be donated. That course of action hurts the motorcycle rider, but of course, if they don’t die and they require extensive medical care, then that puts a big onus on the whole medical system because these people will not pay for the entire costs of their care. Besides, doctors and nurses could better spend their time dealing with other cases.

COVID is a similar problem. First of all, unvaccinated individuals hurt other people, like smokers with secondhand smoke. They also put a significant strain on the healthcare system. This includes not only the infrastructure and the cost to government institutions of having to subsidize the care of these patients, but also includes the hardworking individuals who are taking care of them. But these patients don’t focus on those societal costs. They get sick because they don’t think that what the scientists are saying is important or applies to them, or else that it is political and should be protested.

As humans, we want to have certainty about questions that are important to us. We want to know if there will be another undersea eruption in Tonga. Nobody knows. They ask, how can you not know? Well, on December 11,2021, scientists considered the volcano dormant. Then it blew up a month later. People should understand that science is tentative, but it builds. That’s the responsibility of scientists.

I like to say that science is open-minded because we will accept new ideas and evidence. But it is not empty-headed. It’s not like we don’t know anything. People tend to think that either you know this one fact for sure or you don’t know anything. But we know a ton of stuff. We may just not be 100% certain about the question you are asking right now.

Education in the United States, and in many countries around the world, has been traditionally authoritative, prescribing what you must learn, what is “truth.” But science is not about “truth”; it’s about the best answer we have at the time, which can change with new evidence. People want certainty, especially in difficult situations. If your kid is in the hospital and you ask the doctor what will happen, the most honest doctor will describe the likely outcomes. But even though the doctor is being honest, this is hard for people to understand and many people just don’t want to hear it.

I guess that’s the situation with COVID. People want definite answers until they don’t. If you can tell them the best thing is to get a vaccine and that it will be better for everyone, some didn’t want that answer.

Going back to your paper, you also mentioned “unlearning” the normal ways of communicating science. While the scientist’s role in influencing public behavior may be limited, how can they better generate interest in their sciences so that the public is willing to trust their findings?

Technical scientific publications can be just awful things to read. I call it the anti-narrative, the opposite of a narrative. Instead of describing the progression of thoughts from A to B to C to D – that is, how you thought of an idea or a hypothesis to test, and how you progressively went about it – scientific papers are conventionally written starting with Z, then going back to E, F, G and H for Methods. Then, there’s some kind of a problem statement, but then you jump to the details. It’s just all over the place. It can be really difficult to piece out what you actually did or why. It comes across as merely a bunch of results. In our graduate programs, we don’t frequently teach people how to tell stories about the research. We don’t teach them how to unlearn the desire to push that anti-narrative that gets them published in Nature and Science. To do this, they would need to unpack it, deconstruct it, and reorganize it so that it becomes a story that inserts the human elements.

The best example I know of this kind of storytelling has to do with the team that discovered Tiktaalik, the great Devonian fossil from Greenland that has so many transitional features between typical early aquatic vertebrates and the first ones to go on land. It wasn’t in shape to go on land yet, but it had a lot of those features, which meant it was doing something, adapting to where it was, and doing what it could with the things around it.

The paper on the discovery of this animal, by Edward Daeschler, Neil Shubin, and Farish Jenkins Jr., is beautifully written. But the story of the discovery and why they did what they did is so much more compelling. Neil has this video online and it just knocks you over with details not in the scientific report. But it is so incredibly cool, from how they knew where to look for such a transitional species, and why they could expect it in this location from other discoveries elsewhere in the world, particularly because it had a certain age and environment and particular depth of water and complexity. That’s why they thought this would be a great place to find something. Then, you get into the personal story: how it took them years, how they went and returned several times finding nothing, and how they finally found a quarry to start working on, with one of them ready at all times at the edge of the quarry with a rifle in case a polar bear appeared.

Then, Steve Gatesy was digging and uncovered a part of the back of a skull. He realized what it was. They predicted its existence, and they found it, validating the predictive value of science. It’s not just going out and searching for random things. Being a paleontologist is not just loading up a truck with a bunch of picks and shovels and cases of beer and going out to wander in the desert until you find something. The team knew exactly what they were looking for; they just didn’t know if they would find it. To communicate that aspect of the scientific enterprise to people is so much more important than a simple bland description of the animal, however important it is.

During Bill Clinton’s presidency, the Republicans seized control of the House of Representatives in the 1994 midterm elections and elected Newt Gingrich Speaker of the House. Gingrich decided that with this new class of freshmen Republican congressmen, he would have a campaign to dismantle the federal government. As they were looking over things they could cut, they narrowed in on government agencies they saw as “useless.”

Here, there is a historical contrast between the US Geological Survey and NASA. The geological survey got its budget slashed, but NASA was relatively spared. Why? NASA does some great things and has some space projects that have produced international technological bragging rights. But the Geological Survey covers earthquakes, water quality, minerals, ground shifting, rivers, floods, levees, things that actually affect the lives of ordinary people. So, what was the difference? The answer: The Geological Survey never spent much effort to show people why the work they did was important, while NASA was everywhere. This is the importance of publicizing your work.

About 20 years ago, researchers seeking grants from the National Science Foundation were incentivized to demonstrate a public education component of their project, and that made some people think. At our Museum of Paleontology at Berkeley, we started one website on understanding evolution and one on understanding science. We now have a third on understanding climate change. With this infrastructure, we have been able to outsource our expertise in storytelling, having our people work with researchers to develop a story with them to share on our website as well as their own site. We have an education and outreach group, funded almost entirely by external grants. They are very interactive with people, which is so important to create connections within communities.

In perhaps your most famous example, you gave the advice during the Dover trial that students should consider dissecting their Kentucky Fried Chicken in order to see the pointy part where the individual digit bones fused to form a wing. Do you have any more tips on how to transform complex scientific ideas into comprehensible examples?

I was being a smartass. But I was calling out this pointed part of the chicken wing, which anyone who has eaten chicken will know what I’m talking about, as evidence of transitional change. During that trial, several points in my testimony were designed to pique the interest of journalists reporting the proceedings to the public.

At the end of that case, our planned closing question related to the harm of children being taught intelligent design. I had the response ready. I said: it makes them stupid; it makes them ignorant. It miseducates them about what science is. Those words had exactly the effect I wanted. In 2005, there was no such thing as going viral, but it was reported all over. The judge even quoted it in his decision. This is what you have to do, and you have to do it strategically. The intelligent design folks mostly comprised lawyers, rhetorical specialists, and editorialists who distorted science to make a point. They were not after an honest explanation of what’s going on.

I am not distorting things when I say that teaching children intelligent design would make them stupid. That’s the truth. It would make them stupid about science. Maybe that’s not the worst thing in the world, but it’s a waste of taxpayer dollars, which also resonated with that community.

I’d like to close with one final question. In a few words, how would you convince the scientific community at large that improving their scientific communication is a valuable activity for them?

I’d like to be idealistic, but I’m a realist. After 40 years of faculty meetings, I know that my colleagues are absolutely wonderful people. We can sit in a faculty meeting and all decide that some initiative is a wonderful thing that should be done. But after the meeting, we go back to their labs and return to our daily preoccupations. I’ve got to be realistic, and I’m going to say that our colleagues generally do not act and mobilize unless it benefits them in the bottom line, and the bottom line is going to be research dollars, publications, support for students, and anything else they want or need. And this is perfectly understandable from an institutional point of view.

One of the things that would make sense to them is if they saw that better science communication would get them more support from donors that universities depend on. Now, the complex thing here is that universities don’t bring in donors so that they can fund you, the researcher, but so that they can fund them. There’s a complicated ecosystem around donors, but universities have an interest in controlling the flow of access to their donors.

This is where scientists would have the ability to access donors through storytelling. Development offices don’t have the bandwidth to understand that all the departments would really benefit from financial help, but also that donors love to understand what’s going on at the university, in their classrooms and labs, and how the students are faring. There’s a lot of untapped potential in donors, and I think people would give a lot more if they were allowed to see what happens in the university in a wider sense, rather than just what the development office people want to show them. In this way, the stories of science and scientists could be the route to securing more lasting funding.

Additional reading, recommended by Kevin Padian

- Science Through Story

- ElShafie, S.J. 2018. Making Science Meaningful for Broad Audiences through Stories. Integrative and Comparative Biology 58(6):1213-1223.

Article edited by Jacob P. VanHouten